Ray Bradbury’s The Autumn People and its classic EC horror comics

When renowned science fiction writer Ray Bradbury caught EC Comics plagiarizing his stories for their comic books in the early 1950s, he simply wrote them a letter and asked to be compensated. Bradbury loved comics and was even somewhat chill about the whole thing. The Fahrenheit 451 author quickly got paid, and after subsequent correspondence, a partnership took shape. EC went on to (lawfully) create graphic adaptations of nearly 30 of Bradbury’s stories for horror and sci-fi comics in the years that followed. Sixty years ago this month, eight of those horror strips were collected and republished in a paperback book called The Autumn People.

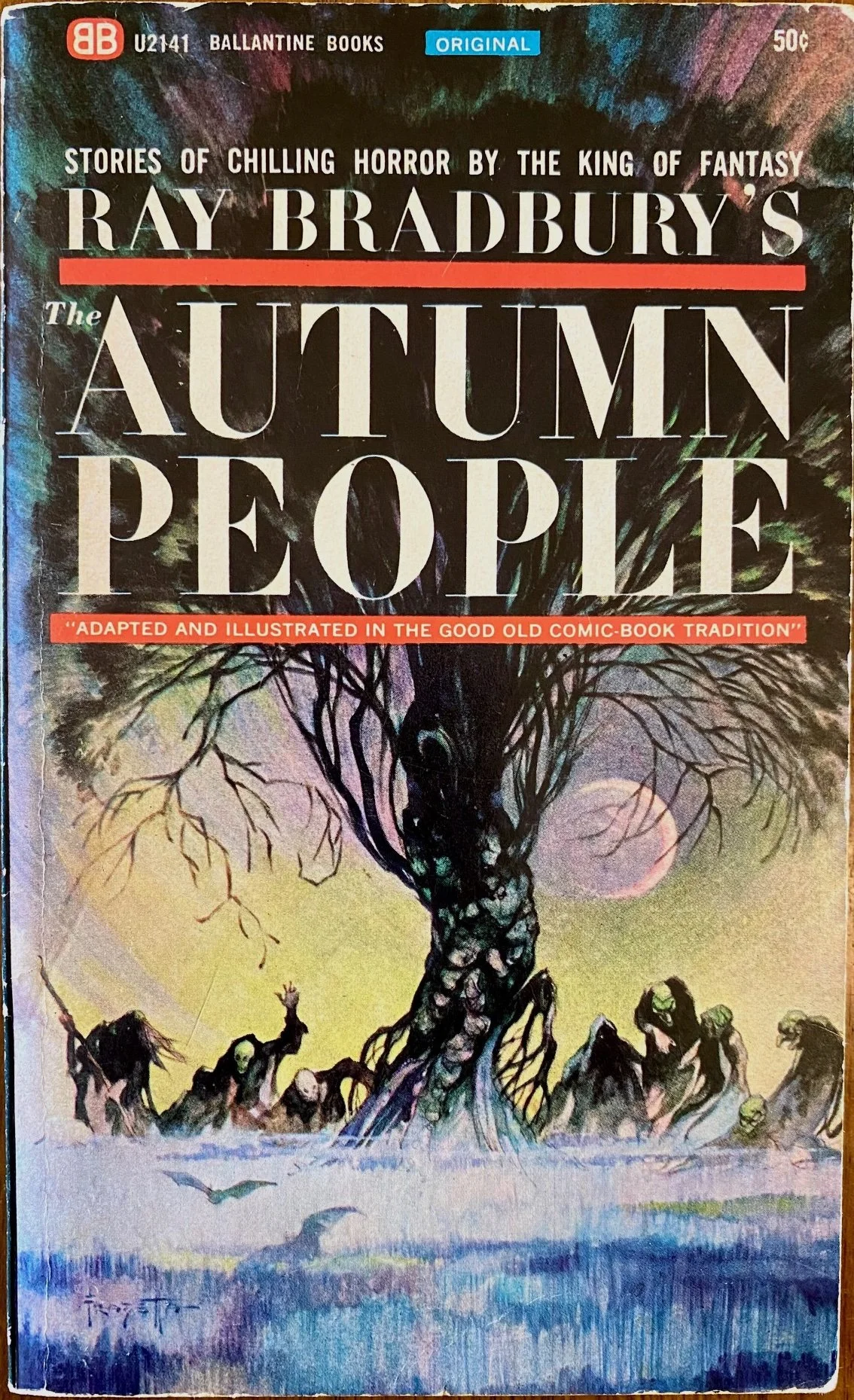

The Autumn People’s black and white comics first ran in EC’s Tales from the Crypt and other objectively great full-color horror comic book anthologies—postwar magazine-style comics that were peddled at newsstands twice monthly for ten cents a pop. But the book, with its appropriately macabre cover painted by Frank Frazetta, saw these spooky vignettes packaged in proper mass-paperback format for the first time. In October of 1965, booksellers slotted The Autumn People on shop shelves alongside Bradbury’s traditional horror and sci-fi collections such as The Illustrated Man and Dark Carnival.

William Gaines had taken over the American publishing house EC Comics in 1947 after its founder, Gaines’s father Max, was killed in a boating accident at Lake Placid, New York. Bill hired writer/editor/artist Al Feldstein in 1948, and Feldstein discovered that he and Gaines shared a love for horror/mystery radio programs as kids, minus the probably intrusive advertisements for Lipton tea. Feldstein convinced his boss to experiment with publishing horror comics.

In Tales from the Crypt and other horror, sci-fi, and crime titles such as The Haunt of Fear and Crime SuspenStories, EC’s pulpy, hyper-violent stories about werewolves, vengeful undead, and serial murderers repelled religious fanatics and other completely boring people all over the United States. But these comics earned EC tons of new readers. The titles inspired shameless copycat publishers, and the horror genre became pivotal to the company’s success.

“Comics were a huge business in the pre-TV times,” reports comics historian Jim Trombetta in The Horror! The Horror! Comic Books the Government Didn't Want You to Read. “Of the eighty million comics that were released each month in the United States and Canada during the early fifties, a quarter were horror comics.”

As I wrote for Hyperallergic in 2017, EC’s crime and horror comics made the organization a target of a national censorship campaign against the art form that emerged in the 1940s. Critics singled out depictions of violence and pretty much anything else that was interesting in the pages of their superbly illustrated comics. The panic gained steam thanks to the dubious “research” published by Dr. Fredric Wertham that suggested that juvenile delinquency and reading comics were connected. This has never been true, and more than a half-century later, comics scholar Carol Tilley proved that Wertham’s work relied on manipulated data.

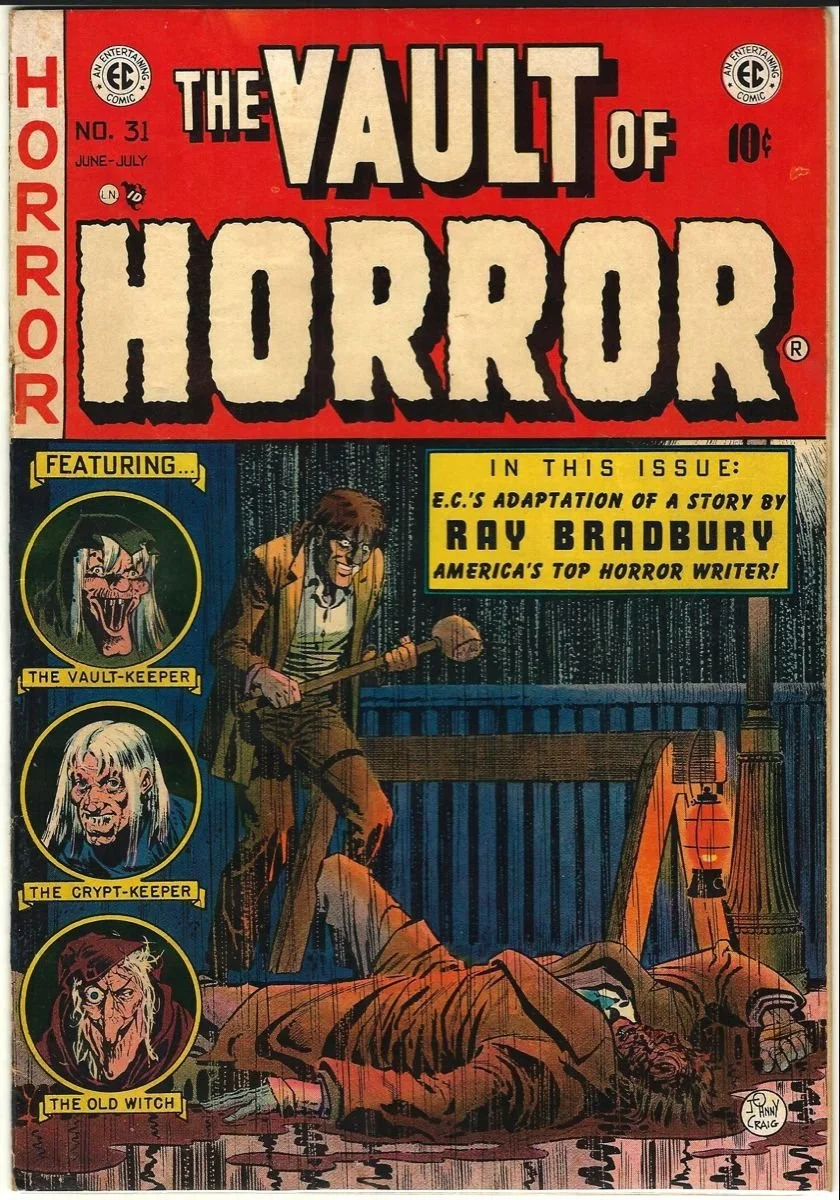

EC’s The Vault of Horror was one such publication in the crosshairs back then. An issue in 1953 included a visually stunning adaptation of Bradbury’s “The Lake” years before it would be reprinted in The Autumn People.

Compared to the gruesome bludgeoning death that artist Johnny Craig created that summer for the cover of The Vault of Horror—complete with a burst that christened Bradbury “America’s Top Horror Writer”—“The Lake,” with its impeccably detailed depictions of nature by Joe Orlando, is quite subdued. In the story, a twelve-year-old boy is traumatized when he loses a loved one to drowning and, years later, is again consumed by grief thanks to an incident during his honeymoon. So, no depictions of heinous murders, but still chilling.

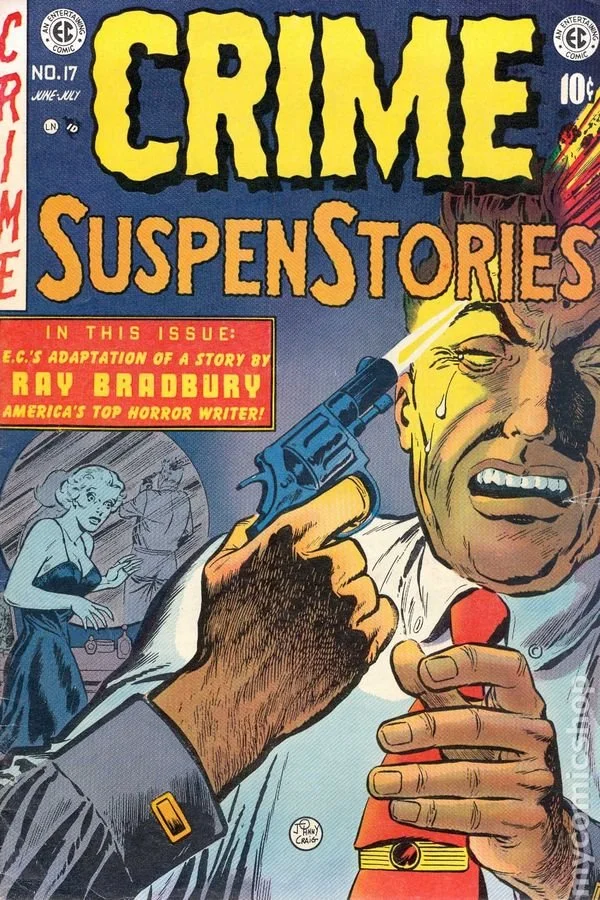

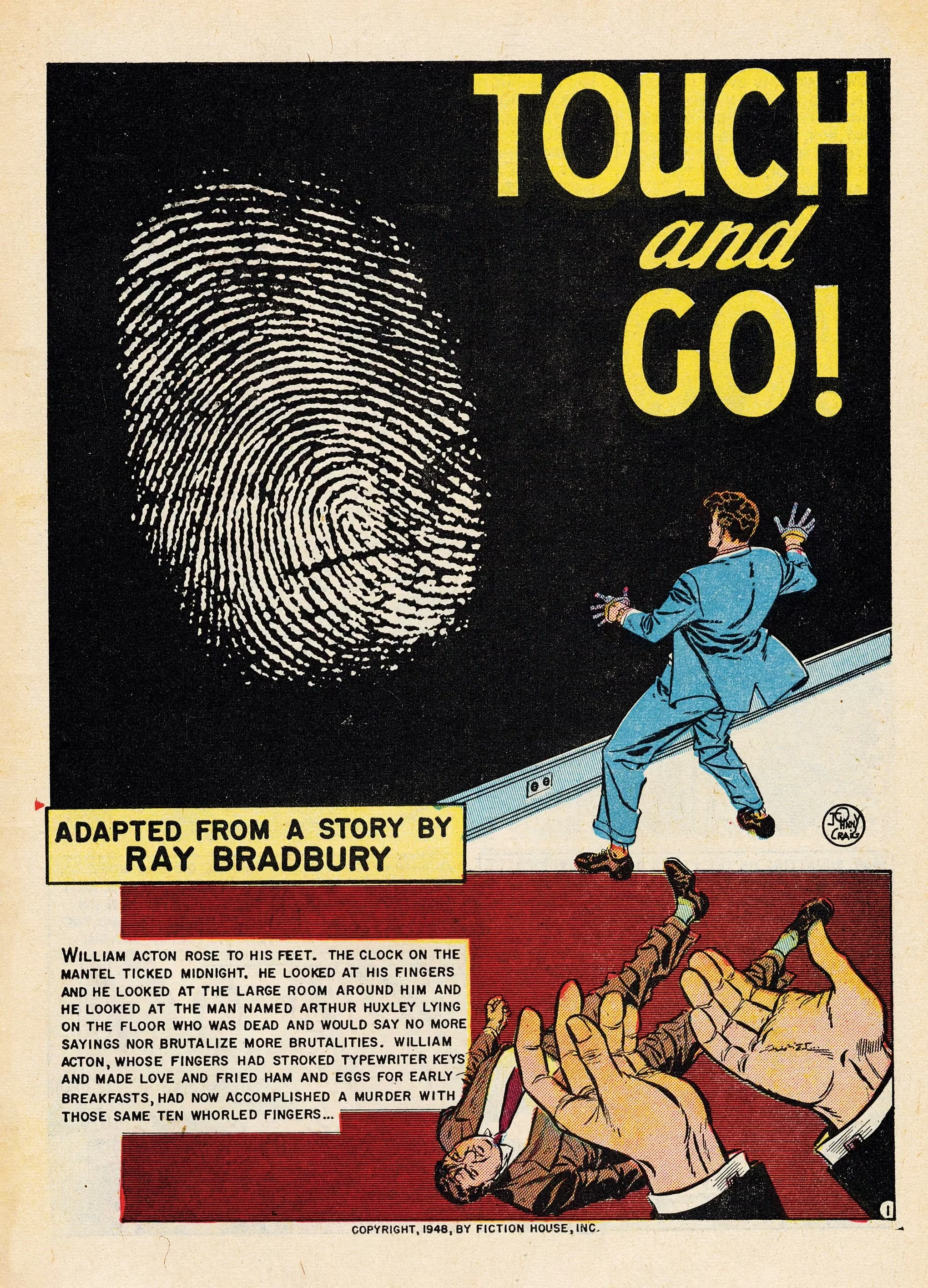

“Touch and Go!”—a Bradbury adaptation drawn by Craig—is far more tense. It appeared originally in Crime SuspenStories, also in 1953. The comic opens with a murderer named William Acton hovering over his fresh victim before a manic house-wide scrubbing of fingerprints ensues so no traces of the crime are left behind. It’s republished alongside “The Lake” in The Autumn People.

Craig’s noirish, mind-bending scenes for “Touch and Go!” explode on the page. They include montages that pair close-ups of a panicked Acton and an assortment of decorative objects that he’s sure need polishing before he makes his exit. EC's adaptation dazzles decades on, even if there is an overabundance of text.

“Feldstein had fallen under the intoxicating spell of writer Ray Bradbury, and while this accounted for many classic stories and a substantial part of EC’s success, it also tended to make the art seem incidental,” writes Greg Sadowski in Four Color Fear.

In his admiration for Bradbury’s prose, Feldstein packed as much of the author’s words as he could into narrative captions. He later said that while adapting him for the comics medium was “the love of his life,” the joke among EC artists “was that I got to write such heavy captions and balloons that all the characters had to be drawn with a hunchback.”

And the unforgiving format of The Autumn People certainly didn’t help, either.

In the wake of the comics witch hunt, EC’s republishing of its comics in paperback books was an effort to gain new readers of their previously banned publications and legitimize an oft-maligned form (even if the company stopped publishing comics in 1956). But of course no one should experience comics that are presented like this.

The Autumn People shoehorned comic book art originally drawn on Bristol Board that was 11 inches wide by 17 inches tall into four- by seven-inch pages. So not only do you obviously lose the work of award-winning colorist Marie Severin, but you also get strips that are suddenly intended to be read horizontally instead of vertically.

Confined to this ludicrous, hostile format, wherein the reader is forced to flip the book on its side, the panels are sawed in half thanks to the gutter. The illustrations are so perversely flattened and squashed that characters’ facial features, for example, once painstakingly penciled and inked by the likes of Craig and Jack Kamen in precise lines that were scalpel-edge thin, bleed into one another so that they’re little more than formless black blots when reproduced for the book. I’d be surprised if any reader who bought The Autumn People immediately became a card-carrying member of the National EC Fan-Addict Club.

Regardless, pre-novelization, “Touch and Go!” has all the jittery energy of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” and your favorite Hitchcock films. (The director regularly reworked crime fiction for his films, and various Bradbury stories were adapted for Alfred Hitchcock Presents.) Craig’s flailing subject washes walls and obsessively swabs flatware that he couldn’t possibly have encountered in the hours before the murder.

“I’m certain I didn’t touch that. I’m certain I didn’t touch that,” Acton repeats to himself while eyeing the house’s interiors in “The Fruit at the Bottom of the Bowl,” Bradbury’s gripping original tale. He spirals further, and even though there aren’t any goblins or beheadings, I’m sure that the kids who thumbed through “Touch and Go!” were properly terrified. But it wasn’t all death and walking corpses.

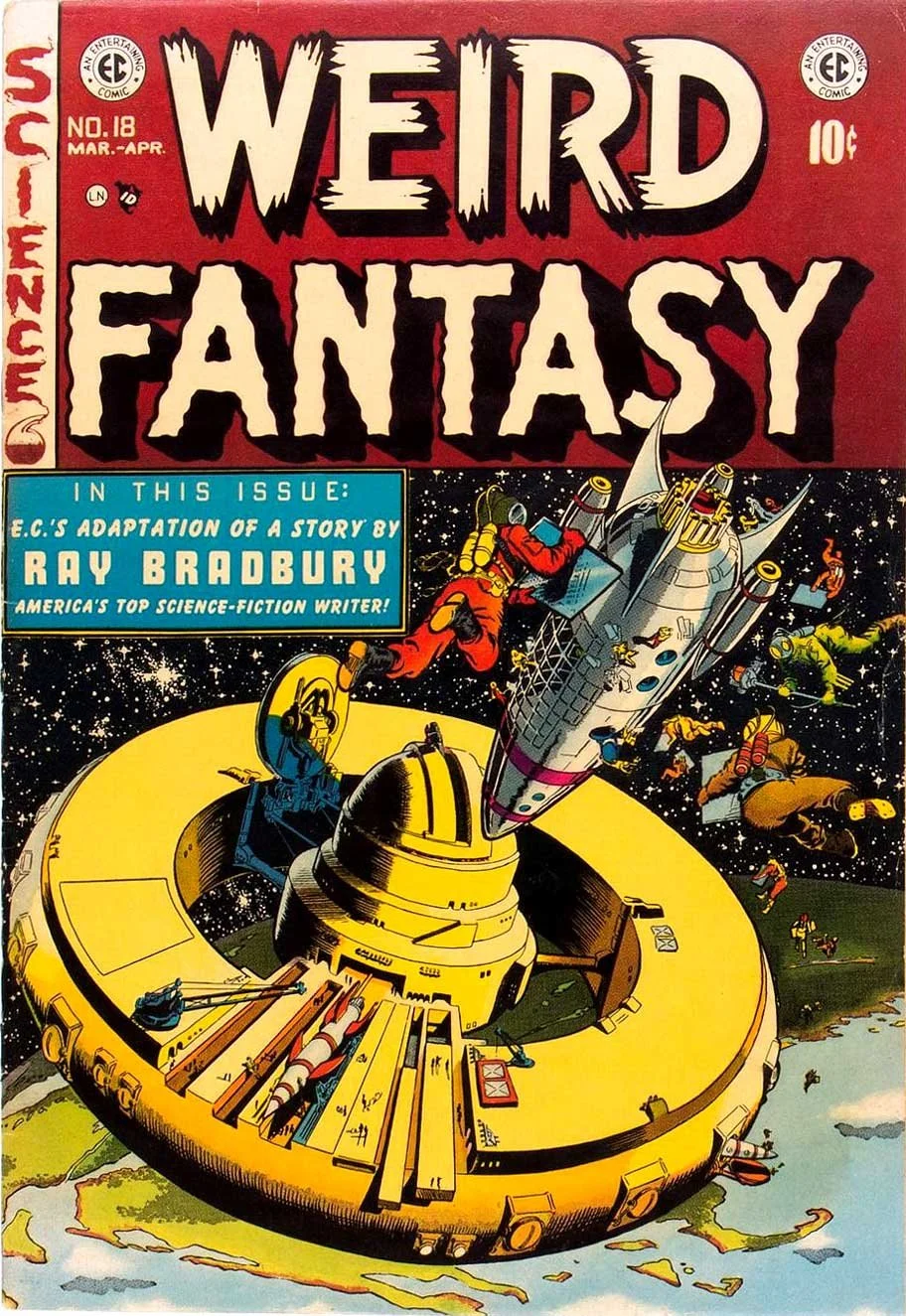

In her book EC Comics: Race, Shock & Social Protest, comics researcher Qiana Whitted examines the “preachies”—EC comics that addressed contemporary political and social issues, such as religious prejudice, racism, and more. When “The Lake” appeared in The Vault of Horror in 1953, Bradbury’s “Zero Hour,” also scripted by Feldstein, ran in a different EC bi-monthly anthology series called Weird Fantasy that year—a title that featured a provocative, now-legendary Feldstein story called “Judgment Day!” that grappled with racial prejudice through the lens of science fiction.

Whitted notes that Bradbury defended the comic when its merits were debated as part of a case brought before the Supreme Court regarding racial segregation and education, and the author was “explicitly representing antiblack racism and segregation in three stories published between 1945 and 1951.”

“(I)t’s not surprising to learn how deeply Feldstein admired his work,” writes Whitted of Feldstein’s love for Bradbury’s stories. She cites an interview that Feldstein gave to Squa Tront, an EC Comics fanzine founded by Roger Hill and Jerry Weist in 1967:

“I was very impressed with his writing style and tried to emulate it, in the comic style,” Feldstein told Squa Tront. “We didn't consciously steal from him, you know, but again, we might have been pretty close.”

EC Comics was perhaps closer to “consciously” lifting Bradbury’s work than Feldstein suggests. In Bradbury’s 1952 letter to William Gaines about plagiarism, he cited a specific Weird Fantasy story illustrated by Wallace Wood in which EC seemed to have mined his prose for material.

“Just a note to remind you of an oversight,” wrote Bradbury to Gaines. “You have not as yet sent on the check for $50.00 to cover the use of secondary rights on my two stories THE ROCKET MAN and KALEIDOSCOPE which appeared in your WEIRD-FANTASY…with the cover-all title of HOME TO STAY. I feel this was probably overlooked in the general confusion of office work, and look forward to your payment in the near future.”

A couple of years later, Bradbury wrote an entirely different kind of letter to EC’s headquarters. He was getting in touch to compliment EC artist Bernard Krigstein’s work on a story of his own in Weird Science-Fantasy #23, which was published after a formal agreement was reached between EC and the author. Bradbury’s letter was excerpted in the “Cosmic Correspondence” fan letters page of a subsequent issue of Weird Science–Fantasy (an issue that incidentally included Bradbury’s “A Sound of Thunder”).

“The Flying Machine is the finest single piece of art-drawing in the comics I’ve seen in years,” Bradbury wrote. “Beautiful work; I was so touched and pleased.”

“The Flying Machine” was Krigstein’s second gig for EC. Like Al Feldstein, who handled all of the adaptations in The Autumn People, the artist was a huge fan of Bradbury’s. In fact, Krigstein contacted Ian Ballantine years later and suggested that he publish a graphic novel adaptation of Fahrenheit 451. Ballantine’s company had by then issued an anthology of stories culled from EC’s Mad magazine, and even though he passed on the Fahrenheit pitch, a deal between Gaines and Ballantine came together in 1964.

That year, Ballantine began to republish in paperbacks EC’s horror and sci-fi comics that had long been out of print. The Autumn People soon made its way into stores.

Cover, The Autumn People © 1965 Frank Frazetta for Ballantine Books. Cover, The Vault of Horror #31 © 1953 Johnny Craig for EC Comics. Cover, Crime SuspenStories #17 © 1953 for EC Comics by Johnny Craig. Title page, “Touch and Go!” © 1953 for EC Comics by Johnny Craig. Cover, Weird Fantasy #18 © 1953 by Al Williamson, Al Feldstein, and Roy Krenkel. I wrote an essay about Ray Bradbury for PopMatters a very, very long time ago (don’t judge).