Will Eisner's graphic novel and City of Clowns

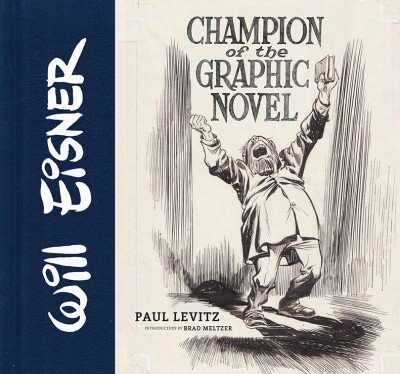

In a widely shared excerpt of a new book called Will Eisner: Champion of the Graphic Novel (Abrams ComicArts) from former DC Comics president and writer Paul Levitz, a lengthy discussion of the roots of graphic novels yields mentions of various watershed works and “titles that helped define the form,” including the woodcut novels of Lynd Ward and Frans Masereel.

Levitz details experiments like those that predated the longform comics of celebrated artist and writer Eisner, specifically his usage of the term "graphic novel.” Levitz cites Richard Corben’s Bloodstar, the work of cartoonist Jack Katz, a 39-page 1970s-era DC Comics horror project, and more. In his preface to the book, Levitz "makes an argument for why [Eisner] was of singular importance, particularly in the evolution of the graphic novel…" He explores the thinking that led to Eisner's A Contract with God, and Other Tenement Stories, a book-length collection of four hand-lettered, sepia-toned interconnected comics stories first published in 1978.

"Contract was centered in a form that evolved from comic books," writes Levitz. "Eisner had spent a lifetime learning the tools a cartoonist could use to communicate with different people in many different ways, and he brought them all to A Contract with God to make it something new without moving it too far from its roots in comics. He wanted a new audience, but there was a recognizable continuity with what came before, too."

Set in or relating directly to a single tenement building and its community of urban dwellers in the Bronx, New York, A Contract with God was Eisner's attempt at using sequential art to produce something as weighty as a novel at the time. In a 2006 edition from W. W. Norton & Company, Eisner suggested in his introduction that he was "a graphic witness reporting on life, death, heartbreak and the never-ending struggle to prevail...or at least to survive." Those elements are very much threaded into the Contract story, which follows the course of a man's relationship with God, and how that relationship is weakened when he loses his adopted daughter to an illness. It's a semi-autobiographical effort that depicts the pain Eisner encountered when he lost his daughter to leukemia years earlier.

Contract's first several pages, while beautiful, are indicative of the book's illustrated storybook/comics property that is partly responsible for its "very limited impact in the commercial world" that Levitz writes about in chapter seven of Will Eisner: Champion of the Graphic Novel.

Before we get to Contract's first panels and word balloons, there are textured, sketchbook-like visuals of sharp-edged, inexplicably symmetrical rain battering New York City tenement buildings and puddling around Eisner's protagonist while a mischievous stew of varying oversized letter forms is set atop the illustrations. From here, it's grim, but hardly as grim as the rest of the collection's depictions of rape, vivid domestic abuse, and more. Eisner produced a weird, adult-themed blend of drawings and text that had no place in the bookstores where he'd intended it to land. Before it was deemed a comics landmark, A Contract With God "was just a weird, largely ignored picture book when it was released," writes critic Tim Callahan.

I'm working my way through Levitz's broad study of Eisner's impact, which is centered on far more than Contract and snakes through a long history of comics storytelling that is inclusive of artistic peaks, like this post's header image, a resplendent watercolor book cover for 1986's New York: The Big City (Kitchen Sink) as well as lesser-discussed lows, such as the 1940s-era introduction in The Spirit of "stereotypical little minstrel taxi driver" Ebony, the product of "racist shorthand from (Eisner)'s youth." This piece, alongside Levitz's two-chapter deep dive into Contract and its "important influence for the immediate effect it had on other people," are components of a provocative history lesson here. And in the style of Abrams' recent Kirby and Simon book, Levitz's examination is dotted with pencil layouts and oversized, awe-inspiring reproductions of original art.

According to its co-creator Daniel Alarcón, City of Clowns (Riverhead Books) is Peru’s “first literary graphic novel,” one that draws on the same woodcut novels that inspired Will Eisner.

A black and white graphic novel adaptation of Peruvian-American author Alarcón’s 2003 New Yorker story about a newspaper reporter mourning the death of his father, City has the look of illustrated prose as often as it does comics. Artist Sheila Alvarado — rightfully billed as a co-author as compared to how Random House's Broadway Books diminished Caanan White's role on its cover for Max Brook's recent Harlem Hellfighters — uses negative space and heavy shadowing well in depictions of loss and isolation, or stretches out wildly with surrealistic visuals. When City of Clowns' journalist, Oscar "Chino" Uribe, learns that his father has died, the road toward coming to peace with it is fraught with memories of his complicated childhood.

"My father’s dying was not news," writes Alarcón in the original story. "I knew this, and there was no reason for it to be surprising or troubling. At the office, I typed my articles and was not bothered by his passing." City's protagonist reflects on his impoverished youth and a sordid relationship with his father, who left him and his mother for another woman when Uribe was fourteen. Alvarado's art depicts this reckoning with frequent silhouetted figures and visualization of a passage of time that differs stylistically from page to page. A clothesline stands in for a storyboard early on, and a subsequent panel that shows Uribe at his desk is bordered by clothespins and rope. Alarcón's disoriented reporter cycles through his deadlines — specifically, the feature he's writing about clowns in Lima — and his thoughts run in spiraling sentences within the swirling cityscape that appears on the book's cover. Such risks prove striking, but the mechanics can use some fine tuning.

Word balloons get clumsy placement in City of Clowns, disrupting the chain of a conversation that's meant to be linear. It's difficult to parse time fluctuations, too, as there isn't really a visual distinction made between Uribe's past and the present storyline.

Whether he's profiling clowns on city street corners or plazas, or mulling the unethical choices his father made years previous, the era is jumbled in the strictly first-person narrative here. I also had trouble finding the context on the political unrest that lingers throughout the story. There are protests, an angry mob that assembles in front of the Congress, mention of a "President...teetering" and cabinet resignations — why? Alarcón is likely referencing a history of governmental repression of journalists in Peru and a 1990s-era wiretapping scandal, but that is never communicated. Alvarado's renderings of the chaos, however, in which a tire fire set by unemployed workers unfurls in pointy, grass-like swirls, are dizzying and electric.

In the City of Clowns afterword, Alarcón discusses the impact of comics journalist Joe Sacco, but this adaptation reminded me — script-wise — of Eisner Award-winning Vertigo comic Daytripper, the protagonist of which was also a reporter whose job was important to the story but was hardly the center of it. It's primarily concerned with life, death, and the relationships in between. From Brazilian creators Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá, Daytripper first ran as single issues in 2010, the year in which the Spanish-language edition of City of Clowns got the treatment that its author thinks it was meant for.

"If this story has always been special to me, it's even more special now that it has been made into a graphic novel with the collaboration of my dear friend Sheila Alvarado," writes Alarcón. "In some ways, I think, this might be its true and definitive form."

—

Note for all Will Eisner: Champion of the Graphic Novel images: THE SPIRIT and WILL EISNER are trademarks owned by Will Eisner Studios, Inc. and are registered in the U.S. Trademark Office. (Header) Front endpapers: Detail, front cover of New York: The Big City, Kitchen Sink Press, 1986. Book cover: From the collection of Ronald S. Sonenthal. Original art for the cover of the first edition of A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories, Baronet Press, 1978. Original art, wraparound cover painting for The Spirit Magazine no. 20, Kitchen Sink Press, 1979.

City of Clowns art © 2015 Sheila Alvarado. Images 1-2 courtesy of Riverhead Books.